Twelve rules for job applications and interviews¶

24th August 2024

This article contains twelve fairly simple rules or principles that job candidates can put into practice, to improve the quality of their applications and their performance in interviews.

Many candidates come into our hiring process at Canonical, and don’t do as well as I think they should. They go wrong in their initial applications or in interviews. Their CVs don’t do them justice. They are unfamiliar with expectations, unprepared for the experience and don’t understand what a prospective employer needs from them.

I see the same mistakes over and over again, a rather sad trail of missed opportunities. It’s a loss for us as well as for the candidates. This is the advice I wish I could have given them.

The rules here are not ‘tips’ or ‘secrets’. They contain advice based on principles. The principles are based upon an understanding of what happens in a candidate’s encounters in a hiring process, and the nature of the relationship between the candidate and the prospective employer.

They are not in any particular order, but several of them are related to each other and I have tried to arrange them in a way that makes sense.

Most of the examples are I use are real, with a few words changed.

1: Answer the damn questions¶

Throughout the interview process, you will be asked many questions. The questions are not there for decoration or asked on a whim. It is staggering how often candidates simply fail to answer questions that they have been asked.

You must answer every single question you’re asked, as best you can. And you must answer the question you were actually asked, not the one you wanted to be asked, or think you should have been asked.

What if…¶

Every question is there because the recruiting team wants to know your answer.

Perhaps you don’t have a good answer for a question. Do your best with it. It’s fine to say: “I am not sure about … but I will do my best with this question”.

Perhaps you don’t understand a question, or you dislike it, or don’t think it makes sense, or think it’s irrelevant, or that it got there by mistake. You might even be right - but you still need to answer it.

Perhaps the answer to a question on the application form is in your CV already. Don’t say “Please see my CV” - just answer the question.

And so on.

Don’t fight the questions¶

Don’t jump to conclusions about why a question is being asked, or try to second-guess what a good answer would be.

It is pointless to take an adversarial approach to the process. Even when it doesn’t seem like it, remember that applying for jobs is a game, and the prospective employer is on your side. You can win the game by helping them to help you, not by fighting them.

If any questions bother you so much that you can’t do that, you should save yourself the stress and withdraw your application.

Pay attention¶

Every question you are asked gives you valuable information about what the company wants. Use it. Take note of the questions you face at each stage; they provide a clue to what you ought to be thinking about for the next interviews.

It’s extremely simple: If you’re asked about your experience, your experience matters. If they ask about your academic history, it means they care about your academic history. If they ask how you approach diversity and inclusion, it means that’s important to them. The deeper they probe, the more they care about it.

(If you have kept a note of the topics that were raised, this gives you material for preparing for subsequent interviews. “I was surprised that in my previous two interviews I wasn’t asked about …” is an excellent way to steer a conversation, especially if you add something like “… and I was hoping that I would be!”)

The same question, twice¶

Candidates are sometimes puzzled or even irritated to be asked the same question multiple times, for example by subsequent interviewers.

Don’t mistake being asked about the same topic for being asked the same question. Different interviewers looking for different things and probing from different perspectives might very well want to discuss the same topic - but that is not asking the same question.

There might be a good reason why you are being asked exactly the same question more than once. Or perhaps it’s a sign of a poorly-designed or executed interviewing process. It doesn’t matter: if you are interested in the job, you still need to answer it, as patiently and willingly the third time as the first.

In other words, just answer the questions.

You can question the questions¶

Of course it’s appropriate to question a question. But do it when someone has the opportunity to respond (not on an application form), and do it courteously, after you have already answered the question.

For example:

When I read the question about academic performance in my high school studies, I wondered if this position were intended for an early-career applicant. Why are you asking about that, when it was so long ago?

But never say something like:

I believe my skills and experience speak for themselves, and are much more relevant than my studies - which were a long time ago.

or:

I don’t need to be a programmer to be a technical writer, why are you asking this?!

or even:

Irrelevant question

2: Show, don’t just tell¶

The more we want someone to know something, the more we want to tell them, but it’s often not the best way to get a message across. What you show is more powerful and memorable than what you tell.

The problem with telling¶

Imagine a candidate who writes this on their CV:

I am honest and hardworking, and a quick learner.

Do we actually learn anything from this? Does it give us any reason to believe that the candidate is not in fact lazy, dishonest and a slow learner?

Here’s another example:

My attention to detail, my software skills in Python and JavaScript and my proven ability to solve problems make me an ideal candidate for this role.

This looks more sophisticated, but in fact it’s even worse. It’s impertinent. (As a reviewer, I will think: “Thank you very much, I will be the judge of that.”)

The value of showing¶

Instead, do your best to show a potential employer the things you want them to see:

Won annual company prize (2023) for diligence and commitment at work.

That’s about something that happened, that shows something about you, that other people recognised and valued.

The way you would naturally speak is a good starting-point for writing about the things you want to show:

After we spotted a bug in our product recently I decided to write some extra test cases, and I was really pleased when one of them caught a new error that would have made it into production last month.

In just one sentence that demonstrates good judgement, initiative, value and pride in your work. If necessary, it can be edited into something terser, e.g. for a CV:

Decided to write extra test cases following a bug discovery; the tests later caught a new error that would have gone into production.

A candidate mentioned having to get up at 5 each morning as a high-school student for a long bus journey. He didn’t need to tell me about dedication, commitment or determination - I could see it for myself.

When you show something instead of telling it, you leave room for the other person to make a judgement. They will hold that judgement much more strongly than if you make it for them.

3: Demonstrate value¶

What you need to demonstrate is value. In a job application that means you need to identify the value you bring and connect it with your actions.

The painfully obvious¶

Imagine this on the CV of an engineer:

April 2021-present Test engineer, Company X (Berlin)

Wrote tests and maintained test suites

Worked with developers and product managers to identify potential issues

Defined testing strategies and objectives

Or you can imagine the conversation, equally dull and unrevealing.

Don’t waste precious words saying the painfully obvious.

Revealing value¶

Value is demonstrated in things that are not already obvious to the person who hears about them. A particular trap candidates fall into is believing that just because various responsibilities are listed in a job advertisement, they must list them in their CV. Those CVs reveal nothing. It’s much better to find ways to show your value:

Set up a weekly “Test engineering office hours”, reducing friction in our process

Introduced one of our teams to TDD; they adopted it with such good results that our CTO asked me to do the same for several other teams

Completely reconfigured our testing infrastructure, aiming to improve build times and lower costs (success on both counts)

And in an interview, when you hear “Tell me more about your work at Company X”, don’t start by thinking of things to say about tasks, responsibilities or activities. Think about the value they brought.

A good way to do that is to use stories (see below). Another way is to think of how things were before and after your contribution:

When I arrived, our test suites were … I could see we needed to improve that so I … Now we have a system that …”.

4: Be personal, specific and concrete¶

Let’s say you want to convey the breadth and depth of your programming experience. You can’t include all of everything. You have to sacrifice something - either scope or detail. Often candidates address this dilemma by opting to use general terms and tones that can embrace everything without having to mention them all by name.

And, they want to give an account of themselves that is authoritative and serious, and so take impersonal perspectives on the things they want to say.

These are both mistakes. It’s better to rely on a personal, specific and concrete approach to get yourself across most effectively.

Which of these would be better in an application or CV?

I am most experienced in JavaScript, which I use professionally on a daily basis, but my favourite language is actually Python. Recently I have learned a little Rust.

or:

Programming skills and experienceJavaScript: advancedPython: intermediateRust: basic

The first frames the skills and experience in the context of the person, and something real emerges from the picture. “But my favourite…” introduces depth and interest. A great deal is packed into very few words: only a certain kind of person has a favourite programming language. You can almost guarantee that an interviewer will be intrigued. I would be curious - about you: “So: why do you like Python?”

It provides specific detail, like “on a daily basis”, that helps understand what it is saying. Its concreteness makes it real, and believable. I can imagine the person.

The second example on the other hand looks as though it is saying something objective but is in fact simply empty. I have no idea what basic, advanced and intermediate mean. It is impersonal, vague and generic. The only thing I learn is that the person is most familiar with JavaScript, less familiar with Python and least familiar with Rust. I might need to ask: “what exactly do you mean by ‘intermediate’?” - but I would feel more impatient than curious.

And which of these two:

I used Requests to find the datasheets in our specifications library on the old website, and BeautifulSoup to clean up the data for import into the new system. I considered deploying the app on AWS, but in the end decided it was simpler and quicker to run it locally.

or:

I am skilled in using Python web tools such as Django and Flask to develop web apps and RESTful APIs. My experience includes using Requests and BeautifulSoup for web scraping. I am adept at deploying apps on platforms like AWS and Heroku, enabling me to build scalable, efficient web solutions.

The second one tries to tell rather than show - but fails even to tell anything very well. “Tools such as”, “my experience includes”, “platforms like” are intended to evoke a wide range of skills that aren’t actually listed, but instead these phrases reduce everything to the same vague, generic level.

A million different Python developers might be able to say exactly the same thing.

The first version on the other hand sticks to a single, actual project, and mentions only the specific tools involved in it. It relates what actually happened. “I considered … but” turns it into a miniature story, in which a protagonist acted.

Perhaps there’s only one person in the entire world of whom this particular story would be true.

It might seem that the author of the first version is at risk of not having their skills noticed - because they aren’t mentioned. That’s simply not the case at all. It’s obvious that someone who has created an app that uses Requests and BeautifulSoup, that they considered deploying on AWS, has a wide range of useful Python and other skills.

We don’t even need to worry particularly if this candidate is familiar with Django or Flask already - they have clearly demonstrated their ability to get things done with Python tools.

5: Show the parts, not the whole¶

Another way to fight off the urge to show everything is to remember that we don’t need to see all of something to know exactly what it is.

If we see the ears of a donkey sticking out from behind a fence, we know perfectly well that the rest of the donkey is there too. It doesn’t occur to us to wonder whether the rest of the donkey might be missing.

Far too often a candidate wastes time trying, in effect, to draw the whole donkey, when you only need to show a part. Recruiters and interviewers are not idiots, and you have to trust their ability to understand more than you tell them explicitly.

If you like, point out that you’re only going to show a part of a much bigger whole that you are also aware of.

Let’s say your interviewer says: “Tell me about your DevOps experience.”

You might be tempted to take a deep breath and launch into a long list of different tools, resources, methods, practices, and roles, hoping that you don’t forget any of them. You would only be able to present a thin and colourless picture of it all.

Or you could take a more confident approach:

I think that in DevOps practices are what matter most, so perhaps I can tell you specifically about some practices that I’ve worked with and that I think were really important. Actually let me start with one practice that I think is more significant than people often think: …

We can see some of the bigger picture ourselves: this candidate thinks in terms of practices as well as tools. They have the confidence to own some opinions about them. They take a critical stance, and are confident enough to say why they think common opinion is mistaken. And we can see all of that even before the candidate has said anything specific at all.

By the time the candidate has finished their discussion of DevOps practices, the interviewer will clearly understand that the candidate is also familiar with many aspects of DevOps that they haven’t even mentioned.

It doesn’t very much matter what exactly the candidate decides to discuss. Just being able to discuss some aspect in depth and concrete detail makes it obvious that their grasp of it is much bigger.

6: Use perspectives¶

Deliberately placing limits on what you discuss is always effective. Another way to do this is to pay attention to the scope of your own approach - choose and use perspectives consciously and deliberately.

Suppose you’re invited to say what you think is significant about open-source software. Topics like this are risky, because they are so open-ended - one could write a book on the subject. They can lead you to respond in unfocused, unmemorable ways. You can avoid this risk by opting to consider the question from some particular perspective, closing down the open-endedness.

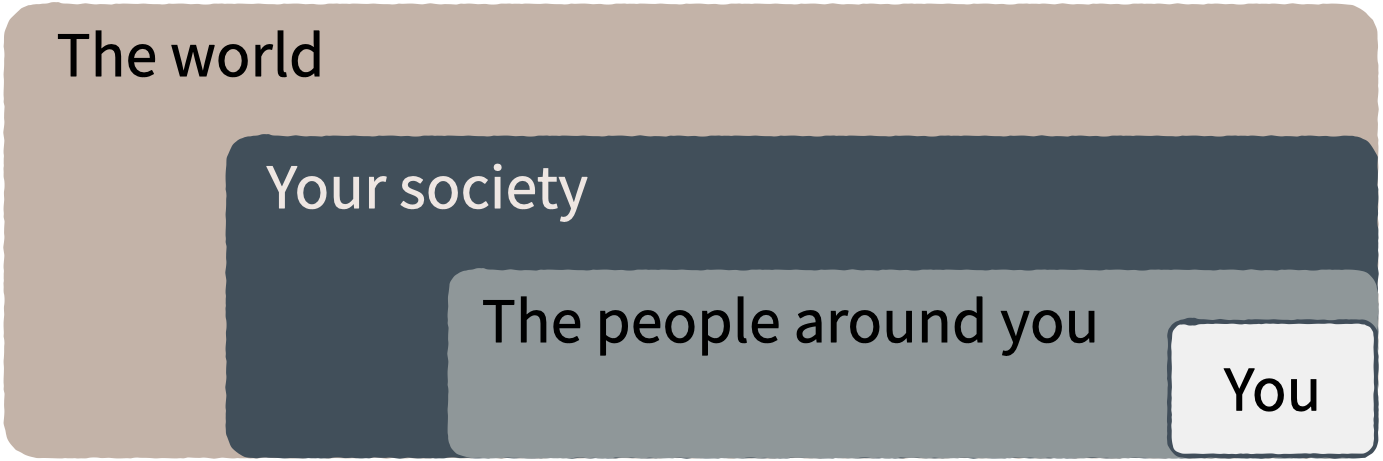

In this case you could decide to answer from the perspective of you as an individual; of the people around you; of your wider society; of the whole world.

For example:

For me, personally, open-source software has meant …

Or:

I think the social implications of open-source software …

It doesn’t matter which perspective you choose, because each one is as valuable as the others. What matters is that you are aware of the choice and make it deliberately.

Naming a chosen perspective makes it clear that you’re doing this deliberately. It’s also a reminder to yourself, helping you neatly round off what you have to say, keeping it within limits that you chose.

Listen for the perspectives that your interviewers use in their questions, and respond appropriately. If I ask “What does open-source software mean to you personally?” and I get an answer that focuses on its global impact, my first thought is that this person probably doesn’t actually have any personal engagement with it.

7: Tell stories¶

One of the things that human beings do best is to make wholes out of parts. Another is to make sense of things through stories.

Stories have meaning. They resonate with us and we remember them. Often the best way to convey a message is via a story. If you tell me a story about something you did, I will learn and understand more about you than I would from any self-description of your character.

Opportunities¶

Look out for opportunities. Sometimes you’ll get an explicit offer to tell a story (“Describe a time when …”). Other times it’s up to you recognise a good opportunity, for example in a question like “Where do you think your strengths lie?” or “Would you say you are a strong manager/good team player/independent worker?”

You might be tempted to say “Yes, I think I am a strong manager because …”, and then list all the things you do, the values you hold, the practices you follow that you think make you fit that description.

Instead, it’s much more effective to say “Yes, and let me give you an example” and then tell your story.

Be prepared¶

Stories need work, so that they can be told in compact, clear ways. You might have the perfect story in your life as an answer to a question, but unless you have already thought about how you will relate that story, you’re not going to do the best job of it. You can ruin a perfectly good story with a rambling, unfocused delivery.

Think up a series of stories, that help show what you want to say. Think carefully about how they work. And rehearse them to yourself, so that they are readily available to you when you need them.

8: Be proud¶

Your interviewers need to see your motivations and values. As usual, you can show these much more powerfully than you can say them. If you can express genuine pride, you offer the interviewer one of the most engaging, warm, rewarding and positive encounters they can have. It’s a window into your heart.

Unfortunately, many of us have grown up in social, educational or work cultures that disvalue pride. We are not encouraged to be proud. Sometimes, pride is treated like a kind of vice, aligned with boastfulness or even arrogance, an unpleasant trait - the opposite of humility.

This is not what pride is. To be proud is to hold and share a value, and stand up alongside it, willing to be measured. To be proud is to be honest, vulnerable and courageous. That’s especially so when you’re proud about what you have done or how you are - because you’re taking the risk of having it denied, or dismissed, or mocked.

The courage it takes to be vulnerable is behind another mistaken attitude to pride. It’s easier and safer to maintain an ironic distance from values and achievements than to embrace them. So, sometimes people don’t allow themselves to be proud - they behave as if they were too cool to be proud, even if what is happening is actually more complicated than that.

Don’t fall into either of these traps when you think about pride. Own your pride. Allow yourself to be proud of your achievements and values. Get used to expressing pride in them. Find stories, and concrete, personal examples that demonstrate them.

Invitations¶

Be alert for invitations to express pride. A question about (for example) your academic achievements is partly about the plain facts of your academic record, but it’s also about how you relate to it. Your pride about a particular academic achievement says a lot to an interviewer.

If the invitation is explicit (“What are you proud of in your studies?”) you really must answer answer that question. Sometimes it’s not explicit (“How did you do in your studies?”) but even then you need to see this as an invitation and opportunity to share what what you’re proud about.

Useless self-deprecation¶

An interviewer refers to a project you were involved in and says: “That’s impressive, it looks like it took some fairly sophisticated Python skills to deliver successfully”.

Do not reply: “Oh no, actually I’m really not …” and try to wave away the admiration (even if your first thought is of all the mistakes, dead-ends and bungled implementations that you came up with along the way, and the numerous people who helped dig you out of your own holes).

Self-deprecation is not humility. It’s false and distancing, a deflection from scrutiny of yourself.

Candidates sometimes say self-deprecating things because they’re rattled by an interviewer’s praise or admiration. Perhaps they worry that they’re accepting something they don’t really deserve, but whatever the reason, it doesn’t make them look more honest and humble. It makes them look evasive and dubious, as if their other apparent praiseworthy attributes might also not be what they seem.

Embrace pride and praise¶

Embrace pride in what you have done, and other people’s praise of your achievements.

Acknowledge both the pride and praise: “Thank you”. Allow yourself to own them: “To be honest, it means a lot to me that other people value that.” Or: “Yes, I am really proud of the results”. Then you can add the other things you want to say: “… and I am proud of the fact that I delivered them despite not being an especially strong Python programmer, and I had to learn a lot while working on it”.

The other side of pride¶

The other side of pride is to be frank about the things you are not proud of. We all have some complications in our stories.

Sometimes, your best answer might have to be something like: “To be honest, when I look back I am not proud of my attitude and attainments in school, but I am proud of how I turned things around afterwards”.

The important thing is to describe it with honesty and to own your mistakes just as firmly as you own your pride.

9: Admit vulnerability¶

An interview is often a high-stress situation. The pressure is on you. Perhaps you’re not an experienced interviewee, or don’t know what to expect, or you’re one of those people who always comes up with the answer they wanted to give five minutes too late.

Whatever form it takes, candidates almost invariably try to hide their vulnerability. It’s a mistake; if you feel vulnerable in an interview, acknowledge and admit it.

Name it¶

The first thing to do is to recognise and name what is going on to yourself (“I am feeling really nervous”). Then, say it out loud, and name it to your interviewer: “I am sorry, I am not used to being in interviews like this and I feel really nervous”. It is absolutely fine to do this.

When you are feeling flustered and realise that you are struggling, naming it has multiple effects. First, it puts your label on it, which is much safer than having someone else name it for you (“This person just talks gibberish!”). Now you own it.

Second, labelling negative things immediately makes them easier to see and deal with; as soon as you have said it you will probably feel calmer.

Third, your interviewer, who is also a human being, will almost certainly understand and empathise with you. Don’t be surprised if the interviewer says sympathetically: “I know exactly how you feel” Or even, after a pause “Actually, this is my first interview on my own and I was feeling a bit nervous too!”

And remember, your interviewer positively wants you to do well.

Be frank¶

You might be taken aback by an unexpected question, technical, professional or otherwise. Name your surprise frankly, and do your best with it:

I wasn’t expecting to be asked that! But I will try to answer it as best as I can: …

I haven’t done that in Go, but I have in Python, and I will do my best to describe the general approach I would take.

I am not sure - I’ll say what I think about this but please tell me if I am on the right track or not.

As well as being honest and open, responses like this show a willingness to engage and find the right way forward. In the workplace, you’re going to have any number of conversations where you don’t fully understand what someone says, or you’re not familiar with a technical topic, or have to deal with something unexpected.

How you respond now shows an interviewer how you will respond if you become a colleague.

Do not invent¶

The worst thing you can do is try to an invent an answer when you don’t have one. It never succeeds in hiding the gaps, and it always makes you look bad. At least if you take one of the approaches above, an interviewer can explain better, or connect the discussion to something you do understand. You have given them a chance to help you.

There is hardly anything more excruciating for an interviewer than to listen to someone who is making things up, talking vaguely about things they don’t really know. It’s generic, unspecific and boring. The interviewer has the sensation of talking with someone who is trying to blow smoke into their eyes to obscure the gaps.

10: Confront weaknesses¶

Every candidate has some weaknesses, and every interviewer knows that. The difference is that some candidates confront their own weaknesses in much better ways than others. When you’re asked about weaknesses, you need to have clear answers that show you have thought about them. It’s an opportunity to demonstrate self-awareness and a constructive approach to self-development.

Consider:

I realised I had a problem with xxx. I discussed it with my manager, who suggested an effective strategy: … That really helped, and since then … I know I still have to work on it, but to be honest I am quite proud of the way I dealt with it.

I have to deal with yyy quite often, and I want to be able to do it better than I’ve succeeded in doing so far. I recently signed up for a training course, which has already helped. I also read <book>, which was recommended to me. I think the next step is for me to …

I found that I was struggling with zzz. I asked a more experienced colleague for advice. She told me (to my surprise) that she had had exactly the same problems, and we came up with a plan that really helped. What was even more surprising was that other colleagues revealed that they also found it hard, and so some of us have been working on it together - it has helped other people too.

These are all excellent examples of confronting weakness directly.

Just as when it comes to feeling vulnerable in an interview situation, when you discuss a weakness, identify the problem before someone else gets to name it for you. Be factual, and show your understanding of its implications. Above all, you need to show how you addressed - or are addressing - it.

It’s very unimpressive when a candidate who is invited to discuss weaknesses deflects or avoids the discussion, or it’s clear that they have never even thought about it. Either way, it doesn’t just make the candidate seem unbelievable, it also makes the interviewer wonder what else they might be hiding, or why they lack the self-reflection to have thought about these things.

Really serious weakness¶

If you have you an on-going, unaddressed problem (“I’ve always had a problem with time-management”) you actually have two weaknesses. One is the problem itself. The other is that you have failed to do anything about it, and probably that is the more serious weakness.

It’s likely that an effective hiring process is going to discover it, whatever you say about it.

11: Do your research¶

A prospective employer doesn’t necessarily expect candidates to be bursting with enthusiasm for a particular role or for the company. You hope that this is going to be the right one for you, and the interview process helps you discover that. But you are expected to be fully engaged and demonstrably serious. Do your research, and use it; talk and ask about what you have learned.

Learn about the organisation, its history and its business model, and key people in it. Learn about its products; you need to be able to name them and say what they do, and ask intelligent questions about them. Look at, and form opinions of, the things that the company makes that are connected to this role.

Do your research on the work. I am regularly astounded to read in interviewers’ scorecards for technical author roles that the candidate has not looked at any of our documentation. What sort of curiosity does that demonstrate?

On the other hand, it’s always a positive sign when one of those candidate says something like “I read some of the documentation for xxx, and noticed yyy”, and wants to have a conversation about it. It doesn’t just show curiosity and interest, it also demonstrates their ability to discuss work.

Look up your interviewers. How long have they been at the organisation, and where were they before? What products and projects are they involved in? What professional topics do they write or speak about?

You can ask them about such things, and it’s fine to do it as directly as you like. “What is it like to work at Company X after working at Company Y?” or “I noticed that you also wrote about <problem x> in <technology y>”.

Awkward topics¶

You are bound to discover some negative opinions about the organisation, its policies, its products or something else. Perhaps you will learn something that raises your eyebrows during the hiring process. Sometimes candidates studiously avoid potentially awkward topics, even while being worried about them, for fear that asking difficult questions might jeopardise their success.

This is a mistake. Firstly, it’s very unlikely that asking a difficult question will count against you, as long as it is done in a respectful and appropriate way. “I read that … - can you comment on that?” should not be an unwelcome question, even if what you are asking about is a criticism or a negative review. Ask those questions in open, straightforward, unembarrassed ways.

And if it turns out that asking a question like that counts against you, then you had a lucky escape, because you do not want to work at an organisation where it’s not safe to ask questions.

12: Be a human being¶

Many of the rules above are about ways for you to be your true self. Lately, new AI tools based on Large Language Models are distorting the way candidates approach job applications. Resist them - throughout the application process, be a human and don’t let an AI tool stand in for you.

Inauthentic CVs¶

There are numerous popular websites that purport to help improve your chances as a job applicant by optimising your CV. Amongst other things, these sites offer CV templates. A very common format that I see a lot comes from a template provided by ResumeWorded.

In fact, it’s not a bad layout. However, the kind of content and the style of writing that they recommend to use in it are stereotypical and inauthentic:

Spearheaded project work and process improvements, enhancing overall service quality by 10%

Drove redevelopment of internal tracking systems, improving efficiency in account management by 15%

Refined product documentation review process, increasing satisfaction scores by 18%

Don’t ever make things up. Over-quantified impact claims like this ring completely false. They are not real or believable. According to ResumeWorded:

Action verbs are important on your resume are vital [sic]. They evoke strong imagery to your reader, […] by using words such as “spearheaded”, “managed” and “drove”.

It’s correct that you should say what you did and why it mattered, and not just list responsibilities, but the advice above and their examples are dreadful. It makes the candidate look like a liar.

No normal person uses language in their speech this way; don’t use it in your CV, unless you also want to sound weird.

Some of these sites provide a service that will ingest your CV and a job description, and rewrite the former (perhaps more accurately, manufacture a fake version of it) so that it best matches the latter. Or, they offer hundreds of bullet points for you to copy and paste into your CV.

These CVs are not just bad, but inauthentic, and the practices encouraged by such websites are dishonest.

LLMs such as ChatGPT or Gemini can also offer to help improve or write (or invent) CVs, with results and advice that are just as unsatisfactory.

These applications will be rejected on sight in any application process that values authenticity.

ChatGPT and friends¶

LLM language and patterns appear in CVs, and also on application forms, written interviews and even in applicants’ conversation. (I have even encountered a candidate trying to use an LLM to come up with answers in real-time during an interview, with predictable results.)

I hire technical authors for software documentation roles. The application form asks candidates to say what they enjoy about technical communication and writing.

When a person describes their enjoyment of something, their eyes light up with pleasure. We look for the same kind of response in candidates’ writing. When it’s real, they want to tell you about it. It comes from the heart, and everyone seems to have their own different, personal way of putting it.

Unfortunately, many candidates refer this question - which is about themselves - to their favourite LLM. Their answers use patterns of words and stereotypical formulations that are instantly recognisable. The language is impersonal and dead (or sometimes, animated by a completely false enthusiasm, which is even worse).

That’s just one example. We see this happening over and over again, across dozens of different roles, and all kinds of questions. The problem is not just that LLM-generated material is generic and weak, it’s also often simply just wrong. For any given topic, an LLM will tend to regurgitate a kind of a lowest-common-denominator conventional wisdom that looks plausible, but misses what is actually at stake.

These are not successful applications.

Being yourself and standing out¶

Successful candidates stand out. Candidates who use AI tools are sometimes barely distinguishable from one another. We repeatedly warn candidates against using AI tools in their applications, but many still fall into the trap.

Confident, experienced candidates who believe in themselves are not tempted to turn to AI tools. It’s the ones who are less sure of themselves who do, hoping for a little extra help

If you don’t believe in yourself, you can hardly expect anyone else to believe in you.

The people who read applicants’ CVs may encounter hundreds of them that exhibit AI traits. I see CVs over and over again that contain literally the same phrases, expressions and claims.

It is creepy to see the same language appearing in applications from people across a range of backgrounds and regions of the world, and disturbing to see individual personality and cultural difference effaced by crude AI tools.

Only a human being will get the job you apply for, so be a human being.

Good luck.